The Cry of the Children

“Pheu pheu, ti prosderkesthe m ommasin, tekna;”

[[Alas, alas, why do you gaze at me with your eyes, my children.]]—Medea.

Do ye hear the children weeping, O my brothers,

Ere the sorrow comes with years ?

They are leaning their young heads against their mothers, —

And that cannot stop their tears.

The young lambs are bleating in the meadows ;

The young birds are chirping in the nest ;

The young fawns are playing with the shadows ;

The young flowers are blowing toward the west—

But the young, young children, O my brothers,

They are weeping bitterly !

They are weeping in the playtime of the others,

In the country of the free.

Do you question the young children in the sorrow,

Why their tears are falling so ?

The old man may weep for his to-morrow

Which is lost in Long Ago —

The old tree is leafless in the forest —

The old year is ending in the frost —

The old wound, if stricken, is the sorest —

The old hope is hardest to be lost :

But the young, young children, O my brothers,

Do you ask them why they stand

Weeping sore before the bosoms of their mothers,

In our happy Fatherland ?

They look up with their pale and sunken faces,

And their looks are sad to see,

For the man’s grief abhorrent, draws and presses

Down the cheeks of infancy —

“Your old earth,” they say, “is very dreary;”

“Our young feet,” they say, “are very weak !”

Few paces have we taken, yet are weary—

Our grave-rest is very far to seek !

Ask the old why they weep, and not the children,

For the outside earth is cold —

And we young ones stand without, in our bewildering,

And the graves are for the old !”

“True,” say the children, “it may happen

That we die before our time !

Little Alice died last year her grave is shapen

Like a snowball, in the rime.

We looked into the pit prepared to take her —

Was no room for any work in the close clay :

From the sleep wherein she lieth none will wake her,

Crying, ‘Get up, little Alice ! it is day.’

If you listen by that grave, in sun and shower,

With your ear down, little Alice never cries ;

Could we see her face, be sure we should not know her,

For the smile has time for growing in her eyes ,—

And merry go her moments, lulled and stilled in

The shroud, by the kirk-chime !

It is good when it happens,” say the children,

“That we die before our time !”

Alas, the wretched children ! they are seeking

Death in life, as best to have !

They are binding up their hearts away from breaking,

With a cerement from the grave.

Go out, children, from the mine and from the city —

Sing out, children, as the little thrushes do —

Pluck you handfuls of the meadow-cowslips pretty

Laugh aloud, to feel your fingers let them through !

But they answer, ” Are your cowslips of the meadows

Like our weeds anear the mine ?

Leave us quiet in the dark of the coal-shadows,

From your pleasures fair and fine!

“For oh,” say the children, “we are weary,

And we cannot run or leap —

If we cared for any meadows, it were merely

To drop down in them and sleep.

Our knees tremble sorely in the stooping —

We fall upon our faces, trying to go ;

And, underneath our heavy eyelids drooping,

The reddest flower would look as pale as snow.

For, all day, we drag our burden tiring,

Through the coal-dark, underground —

Or, all day, we drive the wheels of iron

In the factories, round and round.

“For all day, the wheels are droning, turning, —

Their wind comes in our faces, —

Till our hearts turn, — our heads, with pulses burning,

And the walls turn in their places

Turns the sky in the high window blank and reeling —

Turns the long light that droppeth down the wall, —

Turn the black flies that crawl along the ceiling —

All are turning, all the day, and we with all ! —

And all day, the iron wheels are droning ;

And sometimes we could pray,

‘O ye wheels,’ (breaking out in a mad moaning)

‘Stop ! be silent for to-day ! ‘ ”

Ay ! be silent ! Let them hear each other breathing

For a moment, mouth to mouth —

Let them touch each other’s hands, in a fresh wreathing

Of their tender human youth !

Let them feel that this cold metallic motion

Is not all the life God fashions or reveals —

Let them prove their inward souls against the notion

That they live in you, or under you, O wheels ! —

Still, all day, the iron wheels go onward,

As if Fate in each were stark ;

And the children’s souls, which God is calling sunward,

Spin on blindly in the dark.

Now tell the poor young children, O my brothers,

To look up to Him and pray —

So the blessed One, who blesseth all the others,

Will bless them another day.

They answer, ” Who is God that He should hear us,

While the rushing of the iron wheels is stirred ?

When we sob aloud, the human creatures near us

Pass by, hearing not, or answer not a word !

And we hear not (for the wheels in their resounding)

Strangers speaking at the door :

Is it likely God, with angels singing round Him,

Hears our weeping any more ?

” Two words, indeed, of praying we remember ;

And at midnight’s hour of harm, —

‘Our Father,’ looking upward in the chamber,

We say softly for a charm.

We know no other words, except ‘Our Father,’

And we think that, in some pause of angels’ song,

God may pluck them with the silence sweet to gather,

And hold both within His right hand which is strong.

‘Our Father !’ If He heard us, He would surely

(For they call Him good and mild)

Answer, smiling down the steep world very purely,

‘Come and rest with me, my child.’

“But, no !” say the children, weeping faster,

” He is speechless as a stone ;

And they tell us, of His image is the master

Who commands us to work on.

Go to ! ” say the children,—”up in Heaven,

Dark, wheel-like, turning clouds are all we find !

Do not mock us ; grief has made us unbelieving —

We look up for God, but tears have made us blind.”

Do ye hear the children weeping and disproving,

O my brothers, what ye preach ?

For God’s possible is taught by His world’s loving —

And the children doubt of each.

And well may the children weep before you ;

They are weary ere they run ;

They have never seen the sunshine, nor the glory

Which is brighter than the sun :

They know the grief of man, without its wisdom ;

They sink in the despair, without its calm —

Are slaves, without the liberty in Christdom, —

Are martyrs, by the pang without the palm, —

Are worn, as if with age, yet unretrievingly

No dear remembrance keep,—

Are orphans of the earthly love and heavenly :

Let them weep ! let them weep !

They look up, with their pale and sunken faces,

And their look is dread to see,

For they think you see their angels in their places,

With eyes meant for Deity ;—

“How long,” they say, “how long, O cruel nation,

Will you stand, to move the world, on a child’s heart, —

Stifle down with a mailed heel its palpitation,

And tread onward to your throne amid the mart ?

Our blood splashes upward, O our tyrants,

And your purple shews your path ;

But the child’s sob curseth deeper in the silence

Than the strong man in his wrath !”

Love

We cannot live, except thus mutually

we alternate, aware or unaware,

the reflex act of life: and when we bear

our virtue onward most impulsively,

most full of invocation, and to be

most instantly compellant, certes, there

we live most life, whoever breathes most air

and counts his dying years by sun and sea.

But when a soul, by choice and conscience, doth

throw out her full force on another soul,

the conscience and the concentration both

make mere life, Love. For Life in perfect whole

and aim consummated, is Love in sooth,

as nature’s magnet-heat rounds pole with pole.

I see thine image through my tears to-nigh

I see thine image through my tears to-night,

And yet to-day I saw thee smiling. How

Refer the cause?—Beloved, is it thou

Or I, who makes me sad? The acolyte

Amid the chanted joy and thankful rite

May so fall flat, with pale insensate brow,

On the altar-stair. I hear thy voice and vow,

Perplexed, uncertain, since thou art out of sight,

As he, in his swooning ears, the choir’s amen.

Beloved, dost thou love? or did I see all

The glory as I dreamed, and fainted when

Too vehement light dilated my ideal,

For my soul’s eyes? Will that light come again,

As now these tears come—falling hot and real?

Veo tu imagen a través de mis lágrimas esta noche

Veo tu imagen a través de mis lágrimas esta noche,

y aún hoy te vi sonriendo. ¿Cómo referir la causa?

Amado, ¿eres tú o yo quien me entristece?

El acólito en medio de la alegría cantada

y el rito agradecido pueden precipitarse,

con una frente pálida e insensata,

en la escalera del altar.

Escucho tu voz y tu voto, perplejo, inseguro,

ya que estás fuera de la vista,

como él, en sus oídos desmayados, oye el amén del coro.

Amado, ¿acaso me amas?

¿O vi toda esa gloria como en un sueño,

y me desmayé cuando una luz demasiado vehemente

para los ojos de mi alma dilató mi ideal?

¿Volverá esa luz otra vez,

como ahora vienen estas lágrimas,

cayendo tibias y reales?

De “Sonnets from the Portuguese“(1850)

Mother and Poet

I.

Dead ! One of them shot by the sea in the east,

And one of them shot in the west by the sea.

Dead ! both my boys ! When you sit at the feast

And are wanting a great song for Italy free,

Let none look at me !

II.

Yet I was a poetess only last year,

And good at my art, for a woman, men said ;

But this woman, this, who is agonized here,

— The east sea and west sea rhyme on in her head

For ever instead.

III.

What art can a woman be good at ? Oh, vain !

What art is she good at, but hurting her breast

With the milk-teeth of babes, and a smile at the pain ?

Ah boys, how you hurt ! you were strong as you pressed,

And I proud, by that test.

IV.

What art’s for a woman ? To hold on her knees

Both darlings ! to feel all their arms round her throat,

Cling, strangle a little ! to sew by degrees

And ‘broider the long-clothes and neat little coat ;

To dream and to doat.

V.

To teach them … It stings there ! I made them indeed

Speak plain the word country. I taught them, no doubt,

That a country’s a thing men should die for at need.

I prated of liberty, rights, and about

The tyrant cast out.

VI.

And when their eyes flashed … O my beautiful eyes ! …

I exulted ; nay, let them go forth at the wheels

Of the guns, and denied not. But then the surprise

When one sits quite alone ! Then one weeps, then one kneels !

God, how the house feels !

VII.

At first, happy news came, in gay letters moiled

With my kisses, — of camp-life and glory, and how

They both loved me ; and, soon coming home to be spoiled

In return would fan off every fly from my brow

With their green laurel-bough.

VIII.

Then was triumph at Turin : Ancona was free !’

And some one came out of the cheers in the street,

With a face pale as stone, to say something to me.

My Guido was dead ! I fell down at his feet,

While they cheered in the street.

IX.

I bore it ; friends soothed me ; my grief looked sublime

As the ransom of Italy. One boy remained

To be leant on and walked with, recalling the time

When the first grew immortal, while both of us strained

To the height he had gained.

X.

And letters still came, shorter, sadder, more strong,

Writ now but in one hand, I was not to faint, —

One loved me for two — would be with me ere long :

And Viva l’ Italia ! — he died for, our saint,

Who forbids our complaint.”

XI.

My Nanni would add, he was safe, and aware

Of a presence that turned off the balls, — was imprest

It was Guido himself, who knew what I could bear,

And how ’twas impossible, quite dispossessed,

To live on for the rest.”

XII.

On which, without pause, up the telegraph line

Swept smoothly the next news from Gaeta : — Shot.

Tell his mother. Ah, ah, his, ‘ their ‘ mother, — not mine, ‘

No voice says “My mother” again to me. What !

You think Guido forgot ?

XIII.

Are souls straight so happy that, dizzy with Heaven,

They drop earth’s affections, conceive not of woe ?

I think not. Themselves were too lately forgiven

Through THAT Love and Sorrow which reconciled so

The Above and Below.

XIV.

O Christ of the five wounds, who look’dst through the dark

To the face of Thy mother ! consider, I pray,

How we common mothers stand desolate, mark,

Whose sons, not being Christs, die with eyes turned away,

And no last word to say !

XV.

Both boys dead ? but that’s out of nature. We all

Have been patriots, yet each house must always keep one.

‘Twere imbecile, hewing out roads to a wall ;

And, when Italy ‘s made, for what end is it done

If we have not a son ?

XVI.

Ah, ah, ah ! when Gaeta’s taken, what then ?

When the fair wicked queen sits no more at her sport

Of the fire-balls of death crashing souls out of men ?

When the guns of Cavalli with final retort

Have cut the game short ?

XVII.

When Venice and Rome keep their new jubilee,

When your flag takes all heaven for its white, green, and red,

When you have your country from mountain to sea,

When King Victor has Italy’s crown on his head,

(And I have my Dead) —

XVIII.

What then ? Do not mock me. Ah, ring your bells low,

And burn your lights faintly ! My country is there,

Above the star pricked by the last peak of snow :

My Italy ‘s THERE, with my brave civic Pair,

To disfranchise despair !

XIX.

Forgive me. Some women bear children in strength,

And bite back the cry of their pain in self-scorn ;

But the birth-pangs of nations will wring us at length

Into wail such as this — and we sit on forlorn

When the man-child is born.

XX.

Dead ! One of them shot by the sea in the east,

And one of them shot in the west by the sea.

Both ! both my boys ! If in keeping the feast

You want a great song for your Italy free,

Let none look at me !

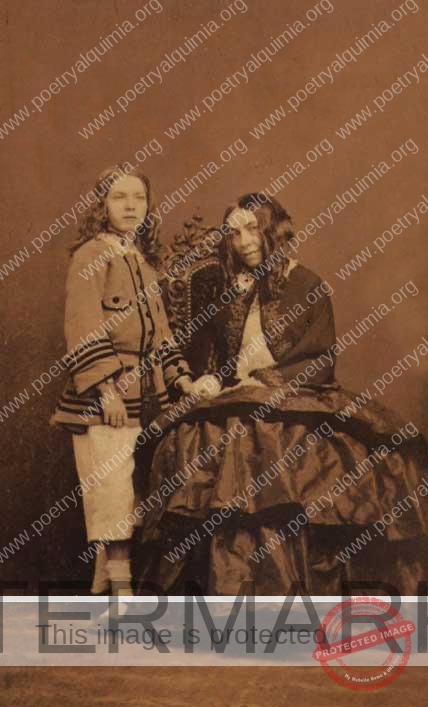

Elizabeth Barrett Browning with her son Pen, 1860

Get Away From Me

Depart from me, although as always,

I stay in your shadow.

And never, alone,

lifting me in the same thresholds of life

hidden, I can control the impulses

my soul, nor raise his hand as before,

toward the sun, quietly, without it perceives

I tried so far away: contact

your hand in mine.

This land width

that would separate the target, in my

leave your heart, beating double. Throughout

I shall do or dream you are present, as

taste in wine grapes.

And when

for me I pray to the Lord in my prayers your name

listening and in my eyes is mixed our tears.

Aléjate de mi

Aléjate de mí, aunque se que siempre,

he permanecer en tu sombra.

Y nunca, solitaria,

alzándome en los mismos umbrales de la vida

recóndita, podré gobernar los impulsos

de mi alma, ni levantar la mano como antaño,

hacia el sol, serenamente, sin que perciba en ella

lo que intenté hasta ahora apartar: el contacto

de tu mano en la mía.

Esta anchurosa tierra

con que quiso separarnos el destino, en el mío

deja tu corazón, con latir doble. En todo

lo que hiciere o soñare estás presente, como

en el vino el sabor de las uvas.

Y cuando

por mí rezo al Señor, en mis ruegos tu nombre

escucha y en mis ojos ve mezclarse nuestras lágrimas.

De “The Seraphim, and Other Poems” (1838)

Retrato de Elizabeth Barrett por Károly Brocky, c. 1839–1844

My Heart and I

I.

ENOUGH ! we’re tired, my heart and I.

We sit beside the headstone thus,

And wish that name were carved for us.

The moss reprints more tenderly

The hard types of the mason’s knife,

As heaven’s sweet life renews earth’s life

With which we’re tired, my heart and I.

II.

You see we’re tired, my heart and I.

We dealt with books, we trusted men,

And in our own blood drenched the pen,

As if such colours could not fly.

We walked too straight for fortune’s end,

We loved too true to keep a friend ;

At last we’re tired, my heart and I.

III.

How tired we feel, my heart and I !

We seem of no use in the world ;

Our fancies hang grey and uncurled

About men’s eyes indifferently ;

Our voice which thrilled you so, will let

You sleep; our tears are only wet :

What do we here, my heart and I ?

IV.

So tired, so tired, my heart and I !

It was not thus in that old time

When Ralph sat with me ‘neath the lime

To watch the sunset from the sky.

Dear love, you’re looking tired,’ he said;

I, smiling at him, shook my head :

‘Tis now we’re tired, my heart and I.

V.

So tired, so tired, my heart and I !

Though now none takes me on his arm

To fold me close and kiss me warm

Till each quick breath end in a sigh

Of happy languor. Now, alone,

We lean upon this graveyard stone,

Uncheered, unkissed, my heart and I.

VI.

Tired out we are, my heart and I.

Suppose the world brought diadems

To tempt us, crusted with loose gems

Of powers and pleasures ? Let it try.

We scarcely care to look at even

A pretty child, or God’s blue heaven,

We feel so tired, my heart and I.

VII.

Yet who complains ? My heart and I ?

In this abundant earth no doubt

Is little room for things worn out :

Disdain them, break them, throw them by

And if before the days grew rough

We once were loved, used, — well enough,

I think, we’ve fared, my heart and I.

The Lady’s Yes

Yes!” I answered you last night;

“No!” this morning, Sir, I say!

Colours, seen by candle-light,

Will not look the same by day.

When the tabors played their best,

Lamps above, and laughs below —

Love me sounded like a jest,

Fit for Yes or fit for No!

Call me false, or call me free

Vow, whatever light may shine,

No man on your face shall see

Any grief for change on mine.

Yet the sin is on us both

Time to dance is not to woo

Wooer light makes fickle troth

Scorn of me recoils on you!

Learn to win a lady’s faith

Nobly, as the thing is high;

Bravely, as for life and death

With a loyal gravity.

Lead her from the festive boards,

Point her to the starry skies,

Guard her, by your truthful words,

Pure from courtship’s flatteries.

By your truth she shall be true

Ever true, as wives of yore

And her Yes, once said to you,

SHALL be Yes for evermore.

El Sí de la Dama

¡Si! Os respondí anoche,

¡No! Esta mañana, Señor, he dicho.

Los colores, vistos a la luz de las velas,

No brillan igual durante el día.

Cuando los tambores sonaron perfectos,

Las lámparas arriba y las risas abajo,

Ámame sonaba como algo cínico,

Tanto para el Sí como para el No.

Llámame falsa, o llámame libre;

Y no importa qué luces brillen,

Ningún hombre verá en tu rostro

La incierta pena de mi inconstancia.

Pues el pecado oscila sobre ambos;

(Es tiempo de danzas y no de compromisos,

Y la luz de la promesa destruye la fidelidad)

Abate sobre mí la cobardía que yace en tí.

Aprende a ganar la fe de una Dama;

Noblemente, como las nubes altas,

Valientemente, en la vida y la muerte

Con una noble gravedad.

Guíala por el escenario del baile;

Muéstrale con tu mano los cielos estrellados,

Cuídala con palabras delicadas,

Limpias de cortejo, puras en halagos.

Por tu Amor ella será fiel;

Siempre fiel, como las damas de antaño;

Y su Sí, cuando sea pronunciado,

Será un Sí para siempre.

De “Poems“(1850)

Grief

I tell you, hopeless grief is passionless;

That only men incredulous of despair,

Half-taught in anguish, through the midnight air

Beat upward to God’s throne in loud access

Of shrieking and reproach. Full desertness,

In souls as countries, lieth silent-bare

Under the blanching, vertical eye-glare

Of the absolute Heavens. Deep-hearted man, express

Grief for thy Dead in silence like to death–

Most like a monumental statue set

In everlasting watch and moveless woe

Till itself crumble to the dust beneath.

Touch it; the marble eyelids are not wet:

If it could weep, it could arise and go.

Pena

Os digo que la pena sin esperanza es pena sin pasión,

y que sólo los hombres incrédulos sienten desesperación,

arrebatados por la angustia, en el aire nocturno

ascienden hacia el trono de Dios vociferando conjuros.

Desierto pleno de almas, yace el silencio desnudo

bajo el níveo y vertical ojo del Cielo absoluto.

El hombre de corazón profundo expresa la pena

por sus muertos en el silencio más quedo, mudo,

como una estatua descomunal erguida en eterna piedra,

sin moverse hasta que él mismo yace en la tierra.

tocadlos, el mármol de sus ojos nunca se humedece,

pues si llorar pudiese, también podría surgir y desaparecer.

De “Poems” (1844)

A Thought For A Lonely Death-Bed

If God compel thee to this destiny,

To die alone,—with none beside thy bed

To ruffle round with sobs thy last word said

And mark with tears the pulses ebb from thee,–

Pray then alone,—“O Christ, come tenderly!

By thy forsaken Sonship—and the red

Drear wine-press,—and the wilderness out-spread,–

And the lone garden where thine agony

Fell bloody from thy brow,—by all of those

Permitted desolations, comfort mine!

No earthly friend being near me, interpose

No deathly angel ’twixt my face and Thine,

But stoop Thyself to gather my life’s rose,

And smile away my mortal to Divine!”

Pensamiento por un solitario lecho de muerte

Si Dios te obliga a este destino;

Morir solo, sin nadie junto a tu lecho

Para escuchar con dolor tu última palabra,

Y marcar con lágrimas el vacilante pulso;

Entonces ruega en soledad: ¡Oh, Señor ven con ternura!

Por tu hijo olvidado en la viña de roja desdicha,

Por la vida salvaje que se agita en el mundo,

Por el abandonado jardín donde la agonía

Cayó como una sangrienta marea de tu frente,

Por toda esta desolación, consoladme.

No hay amigos ni lamentos junto a mi,

Ningún ángel se alza entre mi rostro y el tuyo,

Pero os pido: deteneos y arrancad la rosa de mi vida,

Sonríe, al cambiar esta mortal pena en divina eternidad.

De “Poems“(tercera edición, 1853)

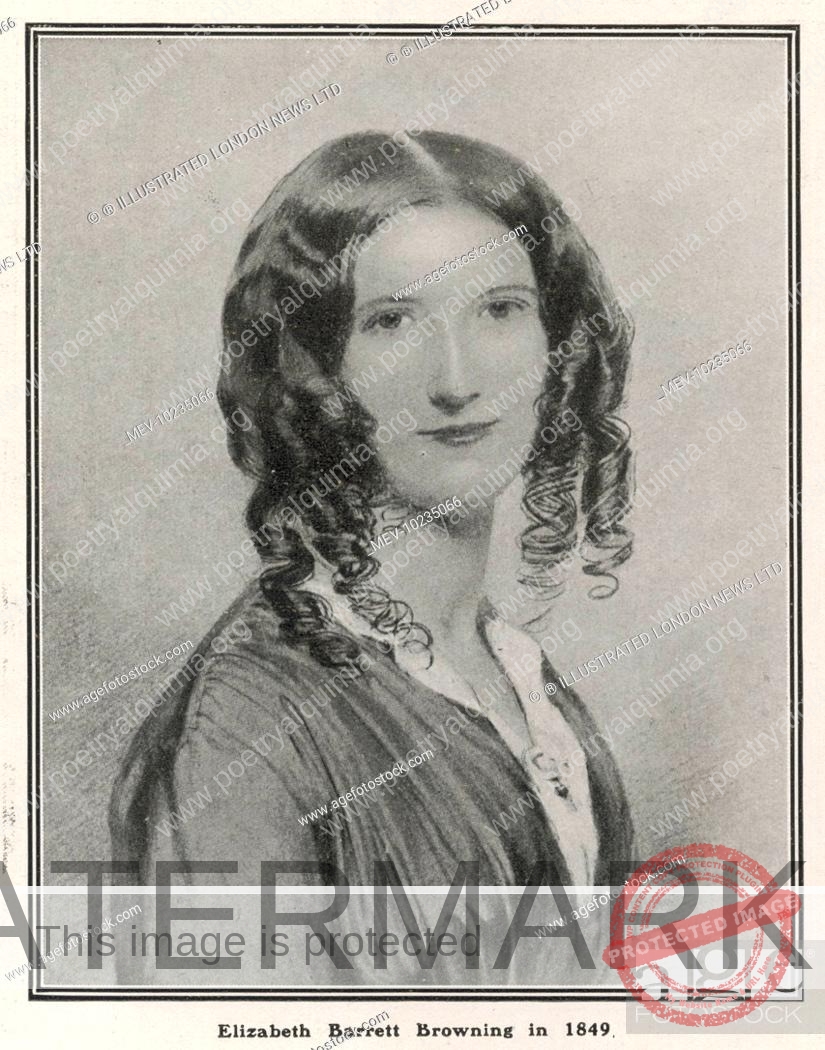

Elizabeth Barrett Browning ( Coxhoe, Inglaterra, 6 de marzo de 1806 – 29 de junio de 1861, Florencia, Italia ).Poeta y escritora. Es considerada una de las poetas mas importantes de la época victoriana. Su obra influyó en autores como Edgar Allan Poe y Emily Dickinson.

Era la hija mayor del matrimonio compuesto por Mary Clarke y Edward Moulton-Barrett, adinerado plantador de azúcar en Jamaica. La familia era propietaria de “Hope End”, una propiedad de casi 500 acres en Herefordshire, entre la ciudad comercial de Ledbury y Malvern Hills. En este entorno apacible, con sus casas de campo, jardines, bosques, estanques, caminos de carruajes y una mansión “adaptada para el alojamiento de un noble o una familia de primera categoría”, Elizabeth, conocida por el apodo de “Ba”, en un principio vivió el tipo de vida que cabría esperar de la hija de un acaudalado hacendado rural. Montaba en su pony por los senderos que rodeaban la finca Barrett, salía con sus hermanos y hermanas a dar paseos y hacer picnics en el campo, visitó a otras familias del condado para tomar té, aceptó visitas a cambio y participó con sus hermanos y hermanas en producciones teatrales caseras. Pero, a diferencia de sus dos hermanas y ocho hermanos, se sumergió en el mundo de los libros tan a menudo como pudo, alejándose de los rituales sociales de su familia. “Los libros y los sueños eran lo que vivía y la vida doméstica solo parecía zumbar suavemente, como abejas sobre la hierba”, dijo muchos años después.

Habiendo comenzado a componer versos a la edad de cuatro años, dos años más tarde recibió de su padre por “unas líneas sobre la virtud escritas con gran cuidado” un billete de diez chelines adjunto a una carta dirigida al “Poeta Laureado de Hope End”.

Antes de que Elizabeth cumpliera 10 años, había leído las historias de Inglaterra, Grecia y Roma; varias de las obras de Shakespeare, incluidas Otelo y La tempestad; porciones de las traducciones homéricas de Pope; y pasajes de Paradise Lost. A los 11, dice en un esbozo autobiográfico escrito cuando tenía 14, “sintió el deseo más ardiente de comprender los idiomas aprendidos”. Excepto por alguna instrucción en griego y latín de un tutor que vivió con la familia Barrett durante dos o tres años para ayudar a su hermano Edward a prepararse para ingresar a Charterhouse, Barrett fue, como afirmó más tarde Robert Browning, “autodidacta en casi todos los aspectos”. .” En los años siguientes revisó las obras de los principales autores griegos y latinos, los padres cristianos griegos, varias obras de Racine y Molière y una parte del Infierno de Dante; todo en los idiomas originales. También en esta época aprendió suficiente hebreo para leer el Antiguo Testamento de principio a fin. Su entusiasmo por las obras de Tom Paine, Voltaire, Rousseau y Mary Wollstonecraft presagiaba la preocupación por los derechos humanos que luego expresaría en sus poemas y cartas. A la edad de 11 o 12 años compuso una “epopeya” en verso en cuatro libros de coplas rimadas, The Battle of Marathon (“La Batalla De Maratón”) que se imprimió de forma privada a expensas del Sr. Barrett en 1820. Más tarde se refirió a este producto de su infancia como “Pope’s Homero hecho de nuevo, o más bien deshecho. La mayoría de las 50 copias que se imprimieron probablemente fueron a la casa de los Barrett y se quedaron allí. Ahora es la más rara de sus obras, con solo un puñado de copias que se sabe que existen. Seis años después escribió “Ensayo Sobre El Hombre y Otros Poemas” (1826).

En el año 1928 falleció su madre.

En 1832, la vida pacífica y segura de los Barrett en su retiro de Herefordshire llegó a un final angustioso. Durante varios años, las plantaciones de Jamaica de la familia Barrett habían sido mal administradas y el Sr. Barrett había sufrido graves pérdidas financieras. Con la perspectiva de un ingreso muy reducido, ya no podía permitirse mantener la propiedad de Hope End y sufrió la vergüenza de tener que venderla en una subasta pública para satisfacer a los acreedores. Los 11 niños y su padre se fueron a vivir temporalmente a Sidmouth, en la costa sur de Devonshire. El motivo de la elección de este pueblo en el sur de Inglaterra puede haber sido la preocupación del Sr. Barrett por la salud de Elizabeth. A la edad de 15 años se lesionó la columna cuando intentaba ensillar su pony.

En Sidmouth, tradujo el “Prometeo Encadenado” de Esquilo. También editó “Poemas Misceláneos” (1833).

Después de vivir durante tres años en varias casas alquiladas en la ciudad costera, los Barrett se mudaron en 1835 a Londres, que seguiría siendo su lugar de residencia permanente. Barrett dio a conocer su nombre en los círculos literarios con The Seraphim and Other Poems,(El Serafín y Otros Poemas)(1838). El libro que comenzó a sacarla del anonimato y a causar aplauso entre el mundo literario inglés y fuera de Inglaterra, siendo el bostoniano Edgar Allan Poe uno de sus máximos devotos.

Justo cuando Barrett estaba siendo reconocida como una de las poetas jóvenes más prometedoras de Inglaterra, tenía tan mala salud debido a la debilidad de sus pulmones que su médico le recomendó que se mudara de Londres y viviera por un tiempo en un clima más cálido. Se seleccionó Torquay, en la costa sur de Devonshire, y allí, junto con varios miembros de su familia que se turnaban para vivir con ella, permaneció durante tres años como inválida bajo la atenta atención de sus médicos. Gravemente enferma como estaba, sufrió un repentino golpe demoledor que la dejó postrada durante meses. La muerte por ahogamiento el 11 de julio de 1840 de su hermano favorito, Edward, que había estado con ella constantemente en Torquay, fue el mayor dolor de su vida.

Cuando regresó a la casa familiar en el 50 de Wimpole Street después de los tres terribles años en Torquay, sintió que había dejado atrás su juventud y que el futuro le deparaba poco más que una invalidez permanente y el confinamiento en su dormitorio. Durante los siguientes cinco años permaneció principalmente en su habitación. Gracias a las herencias de su abuela y su tío, ella era la única de los hermanos y hermanas que era rica de forma independiente. Liberada de todas las cargas domésticas y preocupaciones financieras, era libre de dedicarse a leer y a escribir cartas, ensayos y poesía. Como la perspectiva de encontrarse con extraños la ponía nerviosa, solo dos visitantes además de su familia tuvieron el privilegio de verla en su habitación: John Kenyon, un poeta menor y amigo de muchos poetas ingleses, y la conocida escritora Mary Russell Mitford. A pesar de su encierro, Barrett colaboró en las campañas por la abolición de la esclavitud, así como en las organizadas en favor de la reforma del trabajo infantil, cuya pretensión era, por entonces, “reducir” la jornada laboral de los menores, a diez horas, en aquella Inglaterra industrializada. Su interés por colaborar en la nueva legislación, dio lugar a la creación del poema, “The cry of the Children”, El llanto de los niños, en 1842, en cuyo encabezamiento aparece una cita de la tragedia “Medea” de Eurípides.

Barrett reanudó su carrera literaria, que había sido parcialmente interrumpida durante su grave enfermedad en Torquay. Además de producir un flujo continuo de poemas para su publicación tanto en revistas inglesas como americanas, escribió una serie de artículos sobre los poetas cristianos griegos y otra serie sobre los poetas ingleses. Había llegado el momento de que sus poemas aparecieran en forma de libro, el primero desde The Seraphim and Other Poems de 1838 . La recepción crítica de sus Poemas , publicados en dos volúmenes en 1844, fue tal que a ambos lados del Atlántico, las principales revistas publicaron reseñas elogiosas. Elizabeth Barrett ahora era aclamada como una de las grandes poetas vivas de Inglaterra.

En 1846 se casó en secreto y contra los deseos de su padre, con el poeta Robert Browning, un gran admirador de la obra de Elizabeth que tras leer sus libros comenzó a escribirle cartas de admiración hasta que se casaron.

El matrimonio abandonó Inglaterra para residir principalmente en Francia e Italia, viviendo, entre otros lugares, en Pisa y en Florencia.

En 1849, cuando la autora tenía ya 43 años de edad, la pareja tuvo a su único hijo, Robert.

La estancia florentina de Robert y Elizabeth coincidió con el inicio de la lucha por la unificación de Italia, dando lugar a la creación de: Las ventanas de la casa Guidi – Casa Guidi Windows, de 1851, considerada generalmente, como su trabajo más vigoroso y enérgico, inspirado, naturalmente, en la lucha toscana por la libertad, con sus avances y altibajos.

Publicada en 1851, el título procede de la casa en la que vivían los Browning en la ciudad de Florencia –un antiguo palacio-, en Vía Romana. Elízabeth Browning llegó a apasionarse ante los cambios esperados en el devenir histórico italiano. Durante su primer año allí, escribió “Una meditación en la Toscana”, un poema que registra los acontecimientos políticos y su impacto, vivido por la escritora desde aquellas ventanas del antiguo palacio florentino de piedra, donde vivía.

Su reputación literaria superó con creces la de su poeta-marido; cuando los visitantes llegaban a su casa en Florencia, ella era invariablemente la mayor atracción. Tenía muchos seguidores entre los lectores cultos de Inglaterra y los Estados Unidos. Un ejemplo del alcance de su fama se puede ver en la influencia que tuvo sobre la poeta solitaria Emily Dickinson,. Desde el momento en que se familiarizó por primera vez con los escritos de Barrett Browning, Dickinson la había admirado con éxtasis como poeta y como mujer que había logrado una realización tan rica en su vida. Como homenaje, en el dormitorio de Emily colgaba un retrato enmarcado de Elizabeth Barrett.

Publicaciones :

Algunos de los libros mas importantes de Elizabeth Barrett son :

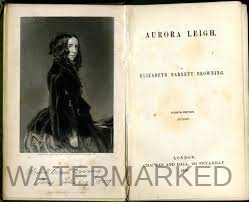

“El Lamento De Los Niños” (1841) “Poemas” (1844), “El Galanteo De Lady Geraldine” (1844), “Sonetos De La Portuguesa” (1850), “Las Ventanas De La Casa Guidi” (1851), y “Aurora Leigh” (1856) y “Poemas Antes Del Congreso” (1860) que fue su último libro antes de que Elizabeth falleciese en brazos de su esposo en Florencia el 29 de junio de 1861.Tenía 55 años. De manera póstuma apareció “Últimos Poemas” (1863).

Las numerosas revistas que informaron sobre la muerte prematura de Barrett Browning hablaron de ella como la poeta más grande de la literatura inglesa. En América, el más extravagante de los obituarios apareció en el Southern Literary Messenger , que la llamó “la Shakespeare entre su sexo” y la colocó entre los cuatro o cinco autores más grandes de todos los tiempos.

En las décadas posteriores a la muerte de Elizabeth Barrett, su poesía comenzó a perder gran parte del atractivo que había tenido para los lectores durante su vida. En 1930, sin embargo, Virginia Woolf, en un artículo del Times Literary Supplement, deploró el hecho de que la poesía de Barrett Browning ya no se leyera y, especialmente, que Aurora Leigh había sido olvidada. Instó a sus lectores a echar un nuevo vistazo al poema, que admiró por su “velocidad y energía, franqueza y total confianza en sí mismo”. “Elizabeth Barrett”, escribió Woolf, “fue inspirada por un destello de verdadera genialidad cuando se precipitó al salón y dijo que aquí, donde vivimos y trabajamos, es el verdadero lugar para el poeta”. Woolf resalta, también, que una de las impresiones más penetrantes cuando se lee, es la sensación de la presencia de la autora, ya que “a través de la voz del personaje Aurora, resuenan en nuestros oídos el carácter, las circunstancias, las peculiaridades de Elisabeth Barrett”.

Actualmente ninguno de los poemas de Barrett ha recibido más atención de las críticas feministas que Aurora Leigh , ya que su tema es fundamental: las dificultades que debe superar una mujer si quiere lograr su independencia en un mundo controlado mayoritariamente por hombres.

Elizabeth Barrett, una de las poetas más importantes de la historia de la literatura inglesa, está enterrada en el cementerio inglés de Florencia.

Enlaces de interés :

https://www.britannica.com/biography/Elizabeth-Barrett-Browning

https://www.poetryfoundation.org/poets/elizabeth-barrett-browning

http://atenas-diariodeabordo.blogspot.com/2019/06/elizabeth-barrett-browning.html